Japanese Lesson: Crises are Created to Centralise Control and Destroy the Middle Class.

The Slow-Growth Experiment as Model for the West - A Primer on how the economy really works

by Richard A. Werner

Switzerland, 21 July 2025. Many observers are puzzled by the dismal economic performance in Europe - which is not getting better, although a new rearmament program may create the illusion of growth. It is argued here that there is a link to the puzzling period of two lost decades of stagnation in Japan, which also created world record national debt for an industrialised country. The analysis goes back to first principles: Only if we understand how economies actually function will we be able to tackle such questions and make reliable forecasts about the future.

Degrowth prescribed for Japan, now exported to Europe

With hindsight we now know that the Japanese recession that began in the early1990s lasted twenty years. In the first decade the recession took most Japan-hands by surprise by its depth and length. Then it came to be used to argue that “structural reform” was necessary for a recovery, although this argument wore thin in the second decade. More and more analysts concluded that my assessment of the early 1990s was correct, namely that the recession had been artificially prolonged by the Japanese central bank.

The great Japanese recession was finally ended in 2013, after Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had won a landslide victory on the unusual election platform of wanting to tackle the too-powerful Bank of Japan – a central bank that had been acting against the interests of the Japanese people for too long. In some speeches Mr Abe was indeed referring to research in my book Princes of the Yen and its policy recommendation to reduce the Bank of Japan’s powers.

Initially, Prime Minister Abe had contemplated a change to the Bank of Japan Law, which had only been changed in 1997 to make the central bank independent and legally de facto barely accountable to anyone. Mr Abe originally joined my recommendation to formally reduce the central bank’s power and independence, and increase its accountability, by revising the Bank of Japan Law again.

This kind of change had earlier been endorsed by a number of (former) fellow LDP politicians and members of the Japanese parliament, including Mr Yoshimi Watanabe, who later became a government minister, Mr Yoichi Masuzoe, who was a member of the Upper House of the Diet, was a government minister later and from 2014 to 2016 was governor of the city of Tokyo, and Mr Kozo Yamamoto, who is a former Ministry of Finance official. They had been readers of Princes of the Yen, which had made a splash in Japan and was widely discussed in the mainstream media in 2001 and 2002. Based on its analysis, they founded the ‘LDP Bank of Japan Law Reform Group’, to which I was formally invited as advisor. Changing the Bank of Japan Law would have been the safest way to permanently derail the reach for ever greater powers that the central planners at the Japanese bank had been working on.

Unfortunately, for some reason, the Prime Minister, who is the grandchild of Nobusuke Kishi, who featured in important chapters of Princes of the Yen, despite his election promises, failed to attempt any change in the Bank of Japan Law. Instead, he focused on the more quickly achievable goal to install a new Governor as head of the Japanese central bank who he thought would push for a more positive monetary policy geared towards greater economic growth. His choice fell on the former vice-minister of international finance at the Ministry of Finance, Mr Haruhiko Kuroda, who commenced as the new governor in March 2013.

I had already confirmed in one-on-one meetings with Mr Kuroda in 1998, when he was still at the Ministry of Finance, and again in 2013, when he had become Governor of the central bank (at the latter meeting, I had four hours in Japan, as I was changing planes, and managed to spend them visiting the Bank of Japan and meeting its governor – an efficient use of my time I thought), that he was fully briefed on the predicament of the Japanese economy – a lack of bank credit creation in the form of loans to the real economy was holding back nominal GDP growth, and this stalling of bank credit creation had been the unchanged problem since the early 1990s. I had explained to Mr Kuroda in these meetings what was necessary for a swift and lasting economic recovery: As I had argued since 1992, no economic recovery would happen until bank credit creation for the real economy (ideally via bank lending for business investment) recovered. Since bank credit creation for the real economy was actually declining in the 1990s, in 1994 I proposed a set of urgent policy measures that the Bank of Japan and Japanese government should adopt, which I called “Quantitative Monetary Easing” or, short, “Quantitative Easing”, to ensure that what I expected would turn into a massive banking crisis could be averted and growth restored swiftly (see my 1991 Oxford Discussion Paper).

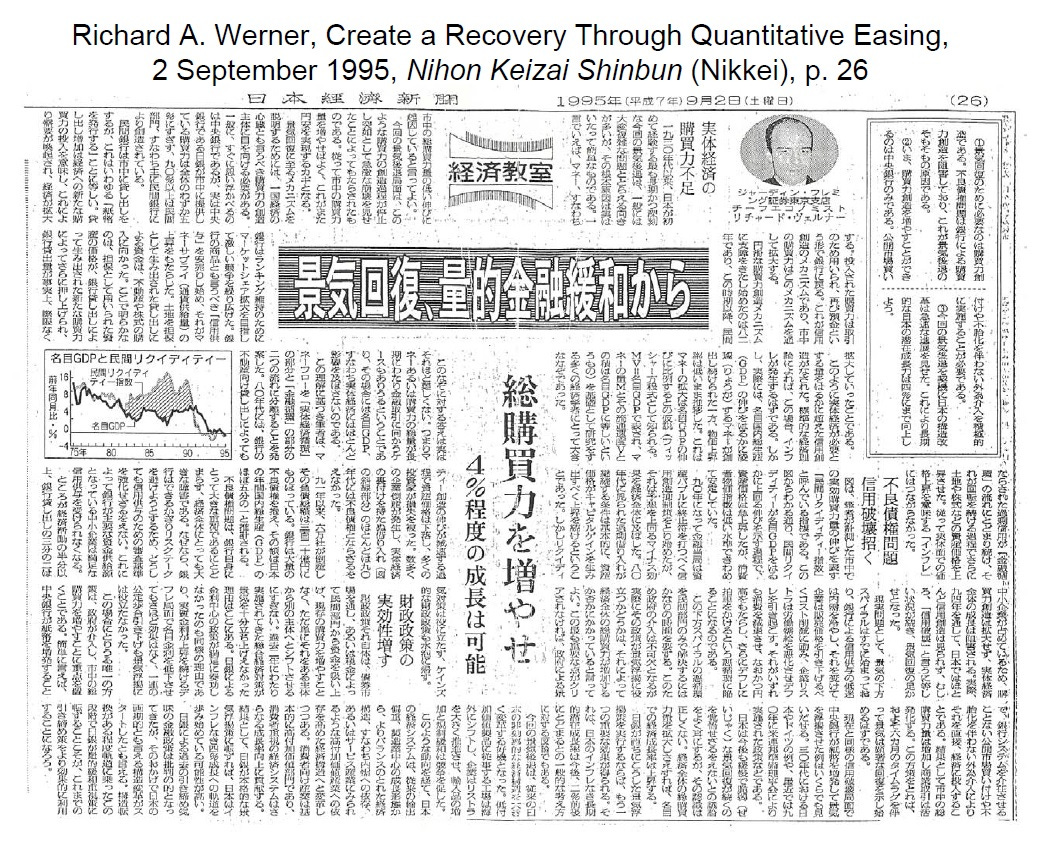

The name “Quantitative Easing” was based on the standard Japanese expression for stimulatory or expansionary monetary policy, which is usually called “easing” (緩和). But most economists were associating that general expression with interest rate reductions. However, I had found that interest rates (the price of money) were not the most important monetary policy transmission mechanism (see my more recent empirical work on this). Instead, it was the quantity of money, correctly measured as bank credit creation that determines economic growth (see my Quantity Theory of Disaggregated Credit e.g. here). To emphasise this quantity aspect, I simply positioned the word “quantitative” ahead of the standard easing expression, and “Quantitative Easing” was born, as published in the leading financial newspaper, the Nikkei (Nihon Keizai Shinbun, 日本経済新聞, whose owner today also owns the Financial Times), on 2 September 1995, and in a series of further articles in the Japanese media and client reports for Jardine Fleming Securities, Tokyo (where I worked as chief economist at the time).

So Mr Kuroda heard first-hand from me the three most important policies that would swiftly create an economic recovery, as I had repeatedly stated since the mid-1990s, namely:

QE1: Central bank purchases of non-performing assets from banks.

The non-performing loans originate from bank credit creation for unproductive use, namely for asset purchases. These caused the prior asset bubble. As soon as such unsustainable bank credit creation ends, asset prices collapse and banks are left with non-performing loans. But this can be remedied swiftly, if the central bank buys them at face value. This QE1 measure addresses the cause of an incipient banking crisis instantly and without using tax payers’ money, by moving the non-performing loans on the banks’ books to the central bank, where they cannot do any harm. This way banking systems can be rescued instantly, and at zero cost to society. This measure also does not create inflation. In fact, it is entirely impossible to cause inflation this way: No new money is injected into the economy – that is, the non-bank sector, by QE1. This form of QE merely constitutes a transaction within the banking system (namely between the central bank and the banks) that cleans up banks’ balance sheets and turns failing assets into pure liquidity. But money creation takes place only when banks inject money into the non-bank sector, which does not happen here. There is no inflation and no fall in the value of the currency. It proves that banking crises do not have to be costly or drawn-out, resulting in recession and unemployment, except when central banks wish it so. Sadly, the Bank of Japan never implemented QE1, and it was Ben Bernanke in the US who did so in 2008 – causing many people to think that all QE is inflation-free, which is wrong, as we shall see when considering QE2:

QE2: Central bank purchases of performing assets from non-banks.

Given the scale of the problem – in 1994 I estimated that 25% of Japanese bank assets were non-performing (based on the amount of bank credit for real estate transactions since 1995) – it was apparent to me that bank loan officers would not increase bank credit, even after their banks’ balance sheets had been cleaned up by the central bank via QE1. The reason is human nature: They would still suffer from “shell shock” from the enormous amount of non-performing loans they had caused and thus would remain cautious for a while. Hence I devised a method by which the central bank can force banks to create credit. This happens, when the central bank engages in asset purchases from non-banks. Normally, central banks exclusively deal with the banks or the government, but not the non-bank sector. My QE2 proposal of 1995 was that the Bank of Japan should simply purchase land in Tokyo and turn it into public parks and green areas accessible to the public. Tokyo is not a very green city and could do with more recreational green space. I was sure that the real estate market was going to collapse for many years to come without the proposed QE policies. This particular measure of QE2 would achieve several goals simultaneously: As the sellers of the land – mostly firms or individuals other than banks – instruct the central bank to receive payment in their bank accounts, the central bank would instruct their bank to credit their current accounts. Since the instructions came from the central bank, banks be forced to newly create this credit in the seller’s account, thus expanding the money supply. In return, the banks would receive a credit in their account with the central bank (known as ‘reserve accounts’). This QE2 proposal is thus a way for the central bank to force a bank credit expansion, an expansion in the money supply and hence an increase in economic activity. It is ideal in situations of recession, shrinking GDP and deflation. Deploying QE2, one can exit such a depression swiftly and stage a strong recovery.

Later in 2013, Bank of Japan governor Kuroda began implementing QE2, which he came to call “Qualitative and Quantitative Monetary Easing”, or “QQE”, in order to distinguish it from the “Fake QE” policy of his predecessors, implemented from 2001 to 2006.

QE3 (fake QE): The central bank purchases performing assets from banks.

During most of the 1990s, the Bank of Japan argued that my QE proposals were “nonsense” and would not work, or could not be implemented. In the early 2000s the central bank then proceeded to implement standard monetarist high powered money expansion by purchasing government bonds from banks – and then wrongly labelling this “quantitative easing” and shouting: “See! It’s not working”, and then abolishing it in 2006. However, in my original contributions between 1994 and 1997 I had already made clear that standard monetarist high powered money expansion would not work. Also, such monetarist measured did not require a new name – proving that the Bank of Japan was merely trying to discredit my original QE proposals.

QE2 for stocks

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Richard Werner’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.