Chinese Lessons Part II: The Elixir of Growth & Prosperity

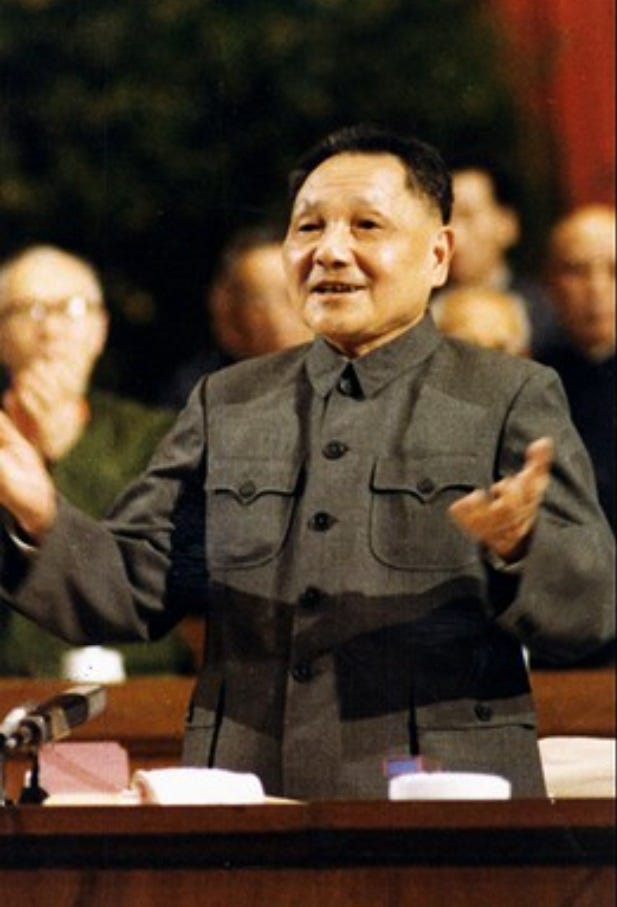

When China got a break: Deng Xiaoping imported the Japanese high growth formula

After nearly three decades of ideological campaigns on the people of China, and likely more than 60 million people killed in the process, even the died-in-the-wool communists had after the death of strongman Mao become tired of party-political programmes (see Part I for more on those). Consequently, it was an uphill battle for Mao’s chosen heir, Hua, to generate any enthusiasm and support. Instead, a growing majority in the upper echelons of the Chinese Communist Party felt keenly that continuity was not attractive, as things had not panned out that well. Instead, the decision-makers ordained that it was time for a change in direction, namely by allowing a reality-oriented pragmatist to take the helm who would focus on delivering results – such as economic development, strengthening the nation and making the Chinese people better off.

Every so often there are moments in world history when the senior decision-makers over nations are neither incompetent agents serving foreign agendas, nor evil, genocidal psychopaths.

The time was ripe for Deng Xiaoping, who had joined the early Communist Party of China in the 1920s and had been on Mao’s Long March in1934. Moreover, he had already been in positions of influence before, but had been unceremoniously deposed several times, sent to labour camps or had otherwise been suppressed. Known as a calm, able and even-handed administrator who had not been involved directly in the cynical anti-human policies of the previous decades, Deng was rehabilitated in 1977 and appointed Vice Chairman of the CCP. He was also appointed Vice Premier of the State Council and member of the Politburo.

Deng picked up the pieces and restored economic order. He was now generally supported, especially as Hua’s unsuccessful attempt to pin the blame for the biggest policy disasters on particular people, such as the “Gang of Four”, had merely driven home the realisation that China had lost many years, even decades in terms of prosperity.

The remainder of 1977 and much of 1978 were a time of preparation for Deng Xiaoping. Then, in December 1978, he gave a key speech, which has since been interpreted as Deng officially taking over the leadership in China.

A New Leader Seeking Results

While Hua officially remained Chairman of the CCP and Premier until 1980 and 1981, respectively, in December 1978, at the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party, Deng Xiaoping was given the platform to declare the policies that China should adopt henceforth.

In his plenary speech, Deng exhorted the audience to “free our thinking”. He announced that the longstanding focus on ideology and the enforcement of party-political dogma would be dropped, and instead China’s leadership would be promoting practical outcomes, namely specifically economic growth and improvements to the country, by implementing economic modernisation due to evidence-based economics. He also announced a programme of economic reform that would deliver growth and prosperity – more on that below.

A key reform implemented in the coming years concerned the process of promotion of future leaders. Instead of basing these on pledges of unlimited loyalty to the party and its official proclamations, as Mao’s psy-ops had trained people, leaders were going to be selected based on their empirical success: The mayor of a town would be chosen from among those who had successfully led villages. The mayor of a city would be chosen from among those who had been entrusted with leading a town and had met or exceeded the goals of economic development. The governors of provinces would be chosen from among those who had proven they could deliver results in leading large cities. Central Committee members would henceforth be chosen from among those governors of provinces who had delivered or exceeded performance results. After a few decades of ideology-based promotions under Mao (the Maoist equivalent to DEI appointments), China’s leadership from 1978 onwards was going to have to deliver results for the people. China had returned to its old merit-based system of state administration, honed over millennia. This move put China in one fell swoop ahead of many Western democracies, where local and central government leaders often are badly educated, unskilled politicos who excel only in giving speeches and propagating ideology, as well as in misallocating resources (just like Mao and his ilk).

The End of the Personality Cult

Deng was a modest person, unlike Mao, and would henceforth stay in second-level positions in the formal hierarchy. From there he manoeuvred to ensure that loyal supporters of his would become Premier, party Chairman or President (Hu Yaobang, Zhao Ziyang and later Jiang Zemin). Deng himself never held the position of Chairman, President, or Premier after Mao’s death. This likely ensured that he could influence policy for longer, at the cost of his ego. But Deng was happy to pay that price. It looks like he was one of those rare people in powerful position who are able to resist the temptations of power, and not a cold-blooded narcissistic psychopath happy to walk over dead bodies. His key position of power was being chairman of the Central Military Commission, to which he was appointed in 1981 and which he held until his retirement in 1990 (he died in 1997). This gave him sufficient control over the enforcement of state power to ensure the implementation of his policies. Despite his lack of formal top positions, Deng was universally recognised as China’s “paramount leader” (Wikipedia) from 1978 to 1990, a phrase used both in China and abroad to indicate his real power, while not holding a formal position reflecting it.

A radical change: Evidence-based policy instead of ideology

How was Deng Xiaoping going to deliver on his promise of economic growth and prosperity?

Deng stated in his December 1978 speech that instead of dull ideological dogma the Chinese leadership would on all levels henceforth “seek truth from facts” [實事求是]:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Richard Werner’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.